Erin Spahr, Social Studies Teacher at Urbana Middle School and Stephanie Gomer, English Teacher at Poolesville High School, were named this year’s Maryland History Day Statewide Middle and High School Teacher of the Year, respectively. The teachers discuss the impact of Maryland History Day program on students.

Erin Spahr, Social Studies Teacher at Urbana Middle School in Frederick, might not be teaching if not for a scheduling error. “I kind of landed in Mr. Holder’s class by accident,” the Maryland History Day Middle School Teacher of the Year said of meeting her own favorite social studies teacher. Between sophomore and junior year, Spahr’s high school switched scheduling formats.

“My school counselor called me in the middle of the summer and said, ‘Your choice is you can either take gym as a junior or you can take AP European history.’ And I went, ‘I’m not taking gym again.’” Spahr calls it “the best decision I ever made.” Spahr says Mr. Holder taught her critical thinking, observing primary sources, and honed her writing skills. “I never in a million years thought I liked European History and when I walked out of his class, I loved European History. I learned how to study in his class.”

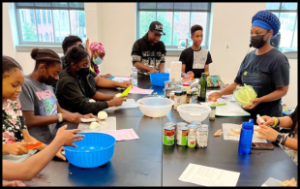

With Maryland History Day, Spahr may be taking up the mantle in terms of helping kids love history who never thought they would. “I think History Day is unique because it gives them an opportunity to explore their interest in history in a unique way, right?” She brings up the vast array of passions kids have; visible in their topic choices ranging from basketball coach Larry Bird and the medicine penicillin, to September 11 and Ronald Reagan. “I have kids this year exploring sociology topics. Like one of them is exploring a serial killer’s effect on society. Other students choose topics tied to their own heritage, such as a student studying India and Goa. “I think it [History Day] just gives them an opportunity to dig into something and research it,” she says. “And I love seeing them get passionate about something they’re personally connected to or interested in.”

Spahr runs Maryland History Day as an afterschool club, which she says “almost tripled in size in just a single year.” She feels that having one of her students win the Special Prize for Civic Action and Engagement “really led to a lot of our students who love history and love clubs and love having a place to belong – but aren’t necessarily kids in other clubs – participating. Like that really kind of got them engaged and got their friends engaged and it gave them a place to come. So they really enjoy coming to my room for an hour every Monday after school and working on their projects together, it’s their social time together.”

One of those students, who also nominated Spahr for Maryland History Day Middle School Teacher of the Year, called her a “phenomenal mentor.” “She consistently goes above and beyond to ensure that her students receive the support they need to excel in their NHD projects,” the student wrote. “Whether it’s troubleshooting technical issues, providing constructive criticism, or offering general mentorship, Mrs. Spahr is always there to help us navigate the challenges we encounter…What truly sets Mrs. Spahr apart, however, is her unwavering passion for teaching and her genuine desire to see her students succeed…For Mrs. Spahr, the true measure of success lies in the personal growth and learning experiences of her students.”

After the competitions ended last year, Spahr hosted a party with food and drinks, where all of the students shared their projects. “Up until that point, we’d only been working on our projects and they’d seen little things and bits and pieces. But then that was the day where we played their [documentary video] document or they shared their websites and they brought in their exhibit boards, and they got to explain their projects to each other,” she says. “To have them share their projects with each other and their passion with each other because they all pick different things. So to share their passions with each other is really cool to see.”

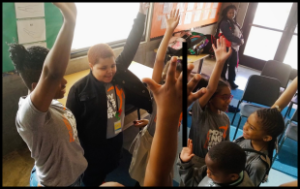

Like her middle school counterpart, Maryland History Day High School Teacher of the Year Stephanie Gomer also enjoys seeing the students’ excitement over their projects. She remembers fondly a group of girls who advanced to the National History Day contest created an exhibit about the 1920s “allowing for alternative lifestyles.”

“They put a curtain on their exhibit,” the English Teacher at Poolesville High School recalls, “and they got so excited like, ‘Miss Gomer. It’s not just like literal, it’s like the figurative curtain that they peeled back on these lifestyles,’” they told her about the people participating in what 1920s America considered “alternative.” Gomer continues: “I remember the excitement of them in class and when they came up. This is why we do it, these moments like this and you’re going to remember this. So that was an amazing, amazing moment, just seeing them work together.”

While Gomer thinks fondly on the students’ excitement, the students recognize their teacher’s own passion. In a nomination for Maryland History Day Teacher of the Year this year, one wrote:

Ms. Gomer is an amazing teacher. She excels in her area and exudes an amazing passion for the subject she teaches. She’s always there for her students, and it doesn’t take much observation to see how much she cares and values each and every one of them I’ve always felt welcome, and she’s never made me feel ashamed or embarrassed when I go in for additional help. She’s constantly encouraging and has a bright, bubbly personality unlike no other. She’s truly my favorite teacher, and there’s no one else I’d rather recommend.

As an English teacher, Gomer “love[s] the interdisciplinary aspect” of Maryland History Day. She says that element echoes the interdisciplinary nature of Humanities House, one of Poolesville’s magnet programs where she teaches. Students take an array of advanced classes in English, history, government, literature, composition, art history, and criticism. Maryland History Day is a part of this curriculum for freshmen (who are assigned papers) and juniors, who can choose their project medium.

Gomer appreciates the challenges Maryland History Day presents the students with. “I think it really just challenges some of the skills that they have, but also lets them develop them further,” she says. “So I think that’s one of the reasons why I love History Day for them.” Students in the Humanities House have strong research skills, but Gomer says History Day “lets them take it to the next level.” The program hones their skills in other ways like collaborating with a group, figuring out next steps, and solving problems with certain deadlines.

Gomer recalls a group of students selected to present at a museum. “That particular group had some group dynamics,” she says, gently referring to ordinary conflict, like one student feeling like their partner isn’t completing their fair share of the work or following up. “I remember having to sit down and we troubleshoot it and talk through some of that and then seeing them after they had that experience,” she says. Since the group advanced to the national level and were selected to present at the museum, they were honored at the Maryland State House this winter.

While working on the project, Gomer says the group “wanted to throw in the towel,” but later “seeing them on the other side, that was great to talk to them.” After visiting the State House, they told Gomer that “It was such an amazing experience.” Gomers response: “This is why I didn’t let you give it up because I knew the potential that you had.”

On the more academic skills honed, Gomer highlights History Day’s focus on primary sources, specifically interviewing them. “Finding people to talk with and interview, I think that’s something that they don’t always get to do or have to do in some of their other research assignments.” Gomer also brings up composing questions, conducting interviews, and incorporating that into a project. “Students find human connection and then find a way to implement that in their projects…I think that’s what makes this like a really valuable experience for them, too.”

Gomer and Spahr will be honored at the Maryland History Day Statewide Contest Awards Ceremony, alongside students, on May 4. As the Maryland History Day Teachers of the Year, they are automatically nominated for National History Day’s Behring Teacher of the Year Award in their respective divisions.

I’m constantly holding policies and procedures up against the light to see how they could be better. Sometimes I feel like I’m back in the day of being a small museum Executive Director and creating exhibits each year by committee. Each year, we’d have volunteers who would write text, then edit their text once it was mocked-up and on the walls, putting post-it notes triumphantly over what they had already written. Trying to make it “just right”. This effort to always look for improvement is one I definitely understand.

I’m constantly holding policies and procedures up against the light to see how they could be better. Sometimes I feel like I’m back in the day of being a small museum Executive Director and creating exhibits each year by committee. Each year, we’d have volunteers who would write text, then edit their text once it was mocked-up and on the walls, putting post-it notes triumphantly over what they had already written. Trying to make it “just right”. This effort to always look for improvement is one I definitely understand.