Fourteen-year-old Saniya Pearson’s family wondered why they heard her yelling. “When we won nationals, I screamed so loud my family ran to my room concerned as to whether there was a fire!” Pearson explained to her family that her team received the Gold Medal in their category at the 2022 National History Day contest, and said family members “were proud, showering me with hugs and kisses.”

Pearson, along with teammates Lillian Merrill and Aliyah Smith, earned second place in their category at the Maryland History Day State Contest before taking the Gold Medal at the National History Day Contest.

“That was one of the best moments of my life,” says Smith. “My mom and I started celebrating like crazy and I messaged Lillian about it. Afterward, I called Saniya and let her know. At first, she thought I was just joking and got a bit confused until she finally realized that we had actually won. My family who had tuned in started messaging and sending congratulations…it was just so surreal.”

For Maryland Humanities’ Maryland History Day program, an affiliate of National History Day, students create original documentary films, exhibits, performances, research papers, or websites exploring a historical topic of their choice on an annual theme. National History Day selected “Debate & Diplomacy in History: Successes, Failures, Consequences” as last year’s theme.

“Starting off in eighth grade, I knew what my topic was going to be: the debate over deaf education between Alexander Graham Bell and Edward Miner Gallaudet,” says Merrill, determined about her project’s content. “When the project first popped up on our radar, I went to Aliyah and Saniya and told them I’d be happy to work with them [after they asked], but I had a project I was going to do.” Without prompting, Smith affirms that the topic was Merrill’s idea.

The year-long work culminates in a state contest before the national competition: advancers to National History Day typically have won first or second place at the state level. The trio, then in eighth grade at Accokeek Academy in Prince George’s County, created a performance.

Merrill discusses how the team integrated their research into the finished project. “We pulled a lot of quotes from various sources, such as the Library of Congress, since we wanted all of their words to be their actual words,” she says. “As we refined it over time, we had them [Bell and Gallaudet] write letters to each other, with me delivering them to the other person.” Merrill also served as the performance’s narrator.

In 2022, Maryland Humanities held its first in-person State Contest since 2019: National History Day’s contest remained virtual. “It was so much fun to check out the college campus, perform live, and find out the results the same day,” Merrill says. “I just loved it all.”

Smith mentions what she thinks makes the program and State Contest special: “Maryland History Day is most definitely different from other experiences as we were able to interact with students outside of our school, outside of our district and compete in a friendly, encouraging environment,” she says. She then shows appreciation for the room Maryland History Day leaves for student creativity. “One of the best parts about creating our MHD project was being able to develop a vision and gather all of the pieces we needed to bring that vision to life,” she says.

Pearson agrees: “What made Maryland History Day different from other experiences I’ve had at school is the experience of creating something and bringing it to life,” she says. “It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience to do something outside of school that I along with my peers, brainstormed.”

While many students mention the extensive work they put into their projects, Pearson doesn’t forget a sense of play. “During our rehearsals, I remember the practice of different accents and tones, and the laughter we had trying to act out these historic people.” She also enjoyed recording the performance on video for the national level. “I loved the videos we took because they brought us closer as friends, laughing and goofing off here and there.”

Smith expresses the nervousness she felt the day of the statewide competition. “Lillian and I were doubtful that we would advance.” Pearson shares a different perspective. “My favorite part of the State Contest, as nerve-wracking as it sounds, was performing live,” she says. “It was the moment our ideas felt real. Although I was anxious about messing up, it was also fun to act out the two opposing sides (Alexander Graham Bell and Edward Miner Gallaudet) with my teammate Aliyah Smith.”

Pearson then recalls hearing the results of the State Contest. “I jumped up and down, shouting with joy! I was so proud to win second place in the competition.“

Annually (with exception of COVID-19’s peak years), all Maryland students win an award honored at the national level visit the State House in Annapolis to receive commendations from delegates and state senators. “Meeting the politicians in Annapolis was an amazing experience,” says Smith. “I never would have thought that I would have the opportunity to do such a thing. Even being able to visit the State House and speak one-on-one with different senators was such an honor.”

Pearson calls the experience “nerve-wracking” but her nerves eventually eased as she spoke with the elected officials. “They all gave us wonderful feedback and even [mentioned] scholarship opportunities!” Other elements of the Annapolis visit held meaning for her. “I loved taking pictures with the Harriet Tubman and Fredrick Douglass statues and reading the engraved history of them.”

Merrill talks about the Annapolis event from the perspective of a citizen of her region. “It was nice to be able to meet the people who are representing my interests,” she says. “They were all very nice, and I have that confirmation that our region is in good hands!”

All three students say they’d recommend that other students participate in Maryland History Day. “Competing in history day was super fun, and a lot of work,” Merrill says.

Pearson talks about how she grew through the program. “If you are someone who is nervous about public speaking or just competing nationally (like me) I’d say this is a perfect way to step out of your comfort zone. Also, it can be a team learning experience if a student chooses to work with a team. It will challenge social skills and collaboration.”

For future History Day students, Smith shares a message or persistence and encouragement: “Even though you might not feel like putting in the work now, even if you don’t make it that far, still do your best and keep pushing. If you don’t make it one year, push even further the next year. You never know what you’re truly capable of.”

It’s not every project where students can select projects ranging from the creation of NBA to women’s fashion of the twenties to space. But that’s the variety Thomas Stavely sees in his Parkdale High School classroom for

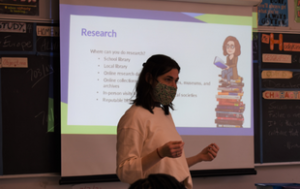

It’s not every project where students can select projects ranging from the creation of NBA to women’s fashion of the twenties to space. But that’s the variety Thomas Stavely sees in his Parkdale High School classroom for  Denise Kresslein, Advanced Academics Teacher at both North Carroll Middle School and Westminster East School in Carroll County, also appreciates the options students have. “I like how the theme provides direction for the students yet is open-ended, to lead to a wide variety of topics,” she says. This year’s theme, selected by National History Day, is Frontiers in History: People, Places, Ideas.

Denise Kresslein, Advanced Academics Teacher at both North Carroll Middle School and Westminster East School in Carroll County, also appreciates the options students have. “I like how the theme provides direction for the students yet is open-ended, to lead to a wide variety of topics,” she says. This year’s theme, selected by National History Day, is Frontiers in History: People, Places, Ideas. Q: What drew you to Maryland Humanities?

Q: What drew you to Maryland Humanities? Q: What is the biggest change you think will come from shifting to general operating grants?

Q: What is the biggest change you think will come from shifting to general operating grants? A: We’ve been doing program-specific grants for a long time with great success. But, our preference has always been to build deeper relationships with our partners that extended beyond funding that specific program. Now that we provide support, we’re able to match our granting activities with our longstanding approach of building meaningful relationships with partners that extend far beyond the moment of time for a single program, furthering our goal of supporting humanities-focused organizations around the state.

A: We’ve been doing program-specific grants for a long time with great success. But, our preference has always been to build deeper relationships with our partners that extended beyond funding that specific program. Now that we provide support, we’re able to match our granting activities with our longstanding approach of building meaningful relationships with partners that extend far beyond the moment of time for a single program, furthering our goal of supporting humanities-focused organizations around the state.  Q: What drew you to sponsor a

Q: What drew you to sponsor a

Q: What will the Maryland History Day for English learners curriculum look like? How will it differentiate from the other Maryland History Day curricula?

Q: What will the Maryland History Day for English learners curriculum look like? How will it differentiate from the other Maryland History Day curricula?

Q: What drew you to Maryland Humanities?

Q: What drew you to Maryland Humanities? In October 2021, the United States (US) reached an inglorious milestone in the history of diseases and illnesses. For the first time, the US recorded 700,000 deaths from the coronavirus-19 disease. This milestone is sobering in many aspects. First, and this is truly sad that

In October 2021, the United States (US) reached an inglorious milestone in the history of diseases and illnesses. For the first time, the US recorded 700,000 deaths from the coronavirus-19 disease. This milestone is sobering in many aspects. First, and this is truly sad that